Fill out the form to contact admissions and learn about your opportunities.

"*" indicates required fields

*Not all programs are available in every state. Consult an Admissions Representative to learn more.

Before Suzanne could learn to write a screenplay, she actually had to un-learn a few ...

Through the Film Connection program, Brian was able to contact his screenwriting ment...

Before Suzanne could learn to write a screenplay, she actually had to un-learn a few ...

Through the Film Connection program, Brian was able to contact his screenwriting ment...

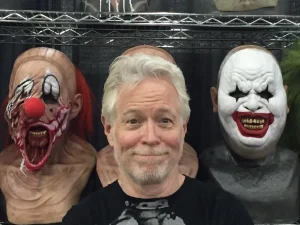

A veteran Hollywood screenwriter, Ron Osborn is a seven-time Emmy nominee known for his work on Meet Joe Black, Moonlighting, Duckman and The West Wing. Given his expertise in the film and television industries, it’s little wonder he’s one of the Film Connection’s most in-demand screenwriting mentors, helping our students frame their scripts to be industry-friendly.

We caught up with Ron by phone recently, and true to form, he offered some powerful insights on the dynamics of story, particularly regarding comedy, drama and the importance of theme. It was just too good not to share. You’re welcome.

“The interesting part that I’ve learned over the years is that the rules between comedy and drama are essentially exactly the same. There’s no real difference. In fact, if you reduce all storytelling to, you know, defining the need and creating the obstacle which is the basis for all conflict, it applies equally to drama or comedy…If I described a film to you where two filmians witnessed a gangland massacre, a cold-blooded shooting of five, six people, and the filmians are discovered and they’re on the run for their lives, is that a comedy or a drama? Invariably, everyone says drama, but that is in fact the basis for the film the AFI voted the best American comedy of all time, Some Like It Hot by Billy Wilder. Because the comedy is not in the jumping off point—the comedy is in how the two protagonists run for their lives, and that’s why [they’re] joining an all-women traveling band and disguising themselves as women. And of course they’re incredibly testosterone-driven…and they’re surrounded by Marilyn Monroe and others and cannot reveal themselves. If they come out as men, they risk their lives. So therein lies comedy… It’s how the protagonist chooses to act to get around the obstacle that brings the comedy, but the jumping off point is always going to be equally as dire, equally as menacing and life-and-death as drama.”

“Protagonists don’t have to be funny. The world around the protagonist can be funny. One of my favorite TV shows—and this is the perfect example—one of the best half hour sitcoms of all time to me is Arrested Development. Jason Bateman is the kind of sane center of that show, if you will, and the least funny character. Everyone around him is hilarious, but he’s kind of the anchor, the one person rooted in some kind of reality and, as such, plays the straight man and yet he is the show’s protagonist, he’s the one we relate to.”

“There’s a little cliché that comedy is tragedy plus time. Comedy is closer to tragedy than it is to drama…When you deal with a subject that is inherently tragic through a comedic approach, then by all means, it can be cathartic. I mean, a co-dependent, destructive male-female relationship can be Who’s Afraid of Virginia Wolf? or it could be Annie Hall. So it’s both of those, and both are very cathartic films…I think the more serious the subject matter, the more potential there is for comedy…The great thing about comedy is it allows us to hold otherwise tragic or taboo subjects at arm’s length.”

I’m a big, big believer in theme. The most important thing you can have besides the situation and the approach and the tone, is theme because theme becomes your compass. It’s always pointing you true north. One of the best examples of theme I’ve ever seen is James Cameron’s Aliens, the sequel to Alien. The theme is the universality of motherhood. Ripley, who we know nothing about in the first Alien, turns out to be a single mom, turns out she promised her daughter she’d return for her 11th birthday, but because she’s been traveling in space at hyper-speed, she has aged differently than her daughter who’s now died of old age by the time she returns to earth. Ripley’s then sent back out into space where they think a colony has been infested with these aliens, and she finds a young girl named Newt, and she is determined to save Newt and redeem herself and not fail her like she feels she failed her daughter.

“Now in the meantime, and this is the brilliant part of the film, she goes up against the queen alien. In the first movie, the alien was basically an asexual parasite that thrives in a host’s body and then lives and grows. Here, we have The Queen; the biggest, baddest alien of them all, and that’s the ultimate antagonist. All the females in the movie are the strongest characters: the female marines and Ripley the protagonist. It is so much about the strength of the female of any species and the universality of motherhood, and that film is brilliant because of that.”

“No one should set out to write a theme. No one sets out to write “war is hell” as a theme. No, you sit down to write a story, and as you’re working it out, you realize what you’re really saying is war is hell. And once you know that, that becomes your compass. Now there’s the danger of playing the theme versus playing the plot, and you don’t want to do that. You want to play the plot and let the theme come out of it. By way of example, going back to “war is hell,” if you have a scene with two soldiers in a foxhole in WWII and they’re talking about what hell they’re going through, that’s playing the theme. But if they’re in a foxhole and it’s winter, and if they don’t start a fire they’re going to freeze to death, but if they start that fire they’re going to alert the enemy snipers to their location and probably get shot, that’s hell. You don’t have to tell me: as the audience, I get it. So you don’t want the theme to dominate; you want the theme to play underneath and guide you, but you want to play the plot and let me, as the audience, get to the theme.”

We recently asked longtime Film Connection mentor Ron Osborn (Meet Joe Black, Moonlighting, Duckman, The West Wing) to tell us a bit more about how he manages his day-to-day life as a screenwriter. What the seven-time-Emmy-nominee sent back was nothing short of spectacular (and funny), so we’ve included Ron’s response here in its entirety. Pay careful attention to how well Ron knows himself and his own habits of mind. He even knows when putting the writing off until the next day works like kindling to his fire.

Now will your writing day look just like Ron’s? Probably not since you’re a different person and a different writer altogether. Nevertheless, look at how you operate, what do you really need to get yourself focused, prepared, and downright hungry to write? If you’ve had some success hacking your own writer’s mind, by all means, leave a comment.

First things first…

If this is the first day of a new script, I have decided it’s so because I’ve spent a number of days/weeks/months/years ruminating on the idea, throwing various brain droppings written on napkins, scraps of paper, yellow legal pad pages, into an ever-growing folder (I currently have seven folders stacked on the left side of my desk of various ideas that are/have been for years in play) – and I don’t begin writing until I’m certain of six things: where I’m beginning the story, my first act break, my mid-point, my second act break, how I’m ending the story and, key to everything in-between, my theme. Assuming I’ve done at least that much heavy lifting – I might start with little more than those six things or I might have a seventeen-page treatment with scenes and snippets of dialogue, as well as another six, eight pages of supporting scene and character notes (as was the case on my last script) – my first day is pretty much the same as the next twenty, thirty, forty, or however many days. To wit…

…my alarm goes off at 3:40 am.

I turn on the coffee by 3:50 am. I’m at my desk, coffee in hand by 4.00 am. This is just the best, most focused time for me to write. It’s as if the entire world has gone quiet for me and I am very aware of its consideration and that I must use this time wisely before said world feels the need to get back to its agenda and tap me on my shoulder, ring on my phone, ding in my texts, or holler from another room. It’s a ritual, I know it’s a ritual, and I’ve come to respect it. Jack Kerouac lit a candle when he began to write, then blew out the candle when he was done. That was his ritual and it focused him.

The first thing I do is make sure nothing extraneous is on my desk. It’s very clean, ordered (I like straight-edges to be aligned at right angles and no, I don’t have O.C.D.), and I like to have a yellow legal pad with a blank page in front of me. Everything else, such as bills, student work to read, the refinance of my mortgage, all go in stacks of priority on the floor that sometimes my chair rolls over. I do all my writing in red ink. I don’t know why. It has to be a very fine-point pen and it has to be red. I read that Prince composed all his film and lyrics in purple ink, so I’m in good company.

After a good two, two-and-a-half hours of work, I always try to fit some exercise in…yoga two mornings a week, spinning on my stationary bike two mornings a week, a light no-frills workout two mornings a week (and really, I don’t have O.C.D.), followed by breakfast spent over the morning paper. The exercise thing I find vital in a line of work that is so stressful and sedentary and solitary; and I find, too, that I’m in a much better frame of mind and more creative on those days when I exercise, than on those days when I do not. It might be a total placebo, but I’ll take what I can get. I would use small animal sacrifice if it gave me the same result.

I’m back at work by 9:00 am.

This writing is the less quiet, more intrusive time and I often have a white noise machine on low. When I’ve hit a brick wall…I like to play computer gin rummy as I ruminate. The upside is, if I just ruminate, I focus too specifically on the problem and demand too much of myself and become more frustrated when answers don’t magically yield themselves. If I tell my brain its main function for the next ten, fifteen minutes is to beat a logarithm, then that gives me permission to not think about the problem, focus on something more immediate, and many times the solution bubbles up from my unconscious. (Walking the dog or a long bike ride can yield the same results.) The downside is, my wife often comes into my office with some such business of the day, only to find me playing a computer card game that causes her to wonder aloud how she can find a way to get paid to do same. I work until 11.59 am whereupon I promptly turn on the television to find out how much further the world has spun off its axis as told to me by an all-knowing, all-news channel (and no, that’s not O.C.D., that’s me just being a news hound needing to check in at noon to see if the world has spun further off its axis) as I make my lunch; I also finish the more in-depth articles from the morning paper over lunch that I didn’t have time to read earlier.

I’m back at work at 1:30 (which includes cleaning the kitchen from breakfast and lunch so as to not further distract me in an O.C.D. kind of way that really isn’t), whereupon I keep writing until 4:30. This gives me a solid eight hours of writing with structured breaks so as to not overload the brain. After that is when I answer most of my day’s emails, return calls that can wait, run errands…

…and I will admit, just as I begin my day of writing in a specific and ritualized way, there is very specific way I like to end said day (and no, this is not O.C.D. because there are enough times when the gods conspire to keep this from happening)…I like to stop writing mid-scene even though I know the rest of a scene…or I know what the next scene is, or I know what the next two scenes are, such that that I could easily keep writing for another twenty, thirty minutes, even an hour, and stretch my page count for the day. But – and this I can’t underestimate – nothing beats sitting down at my desk the next morning, cup of coffee wafting up from off-screen, legal pad with blank page in front of me and red pen in hand, and I know exactly where I’m going to go. That half-scene or scene, or two scenes are worth not finishing the night before if it primes the pump at 4.00 am and prevents me from sitting down with a blank page and nowhere to go. Such a great feeling.

Somerset Maugham was asked what his ritual was when he wrote. And to paraphrase he said, “I write from this time to this time, every day.” Whereupon he was asked, what if he had nothing to write. His response was, “I write my name.” I get it. I couldn’t do it, but I get it. Creativity without discipline is a gun without target.

Screenwriter Ron Osborn has been a mentor within the filmmaking department of the RRFC program for 10 years! With over 40 years of experience, he has amassed an impressive collection of credits for film and television including Meet Joe Black, The West Wing, Duckman, and Moonlighting–garnering 8 Emmy and 2 Writers Guild nominations. I sat down with Osborn to discuss art, life, the future of television, his creative philosophies, and the program.

Very simple question with a complicated answer. I was an art major up through two years of community college. I wanted to be an illustrator, so I transferred to the Art Center/College of Design in Los Angeles, from Santa Cruz originally. My first semester, I had an assignment where I had to use an 8-millimeter camera, and it was my damascene moment. I just thought, “Where has this thing been all my life?” I continued on my illustration track but was taking all the film classes I could take—at the time there weren’t many at the school. Midway through I changed my major to graphics, which had all the film classes. Then a number of like-minded students and myself lobbied to have an actual film major.

By the time I graduated, it was the first semester one could graduate with a film degree, and I was the first film graduate. Ironically, the one thing that they didn’t really teach was [screenwriting]. I discovered I wanted to be a writer late in my stay there, when The Boys Club of America asked us to make a fundraising film for them, and I got [tasked with] writing it, which I had never really done before. That was my second damascene moment where I realized that the core of the message in any narrative is found within a piece’s writing. That the idea is king! I haven’t changed my opinion since. I have directed as well—I’m a member of the DGA—but I don’t get near the creative satisfaction I do from writing.

I was asked back in 1985 to teach, which I did for 36 years. I just recently stopped. I taught introduction and advanced screenwriting.

That was a very anxious and fraught period. I knew nothing about the business. I had no contacts. As the school didn’t have much of a film department at that time, there was no networking with any graduates who came before us. There was no internet. I just started writing. There were two books [that really inspired me]: The Art of Dramatic Writing by Lajos Egri and Screenplay by Syd Field. I was in Syd’s first class, from which he developed the book, and he and I became friends. We even wrote a screenplay together. But to support myself at the time, I was a temp typist, and I gave plasma three times a month and had food stamps. I got an agent about three years out and she suggested I write comedy because it was easier for her to sell a sitcom writer than it was to sell an unknown feature writer.

So, I took a [class on television writing], taught by Gary Belkin, who has a hugely impressive list of half-hour comedies going back to the 60s or so. In the class he took me and another student aside, named Jeff Reno, and said ‘you guys should be partners.’ He felt we had the strongest sense of narrative and comedy. He said that, ‘All things being equal, producers will hire a team over an individual.’ We decided to try it, we wrote a spec script for the best-written show at that time, M*A*S*H. That basically started us off, we were asked to pitch at various half-hour shows, and it earned us an interview at Mork and Mindy, an extremely popular show at the time. We thought we were interviewing for a freelance script assignment, but when we left my agent called and said, ‘hey, they want you on staff.’

Not Briefly. There’s a lot more opportunity to find an agent now. There’s a veracious appetite for content, because of all the platforms that are out there now. All the streaming and cable and basic cable. The agents are looking. One way, more than ever, are the various competitions to enter. Not all of them are created equal. But you can get noticed. The Nicholl Fellowship is probably the most prestigious. Even if you make the quarterfinals in that, an agent will probably read your script. If you make the finals or place; then yes! It can be a way to get attention.

Obviously, I had a lot of exposure to him, but as a staff writer I didn’t interact with him that much. I got to watch him work. He was very impressive. He was incredibly talented and incredibly shy. It was a defense mechanism. He wasn’t just a comic mind, he was profound, extremely well-educated, a great sense of history, he drew from everything. But let me make one caveat here, contrary to the hype, he didn’t adlib scripts. That was put out there by his management. There was a myth that the producers were so impressed by his improvisation skills that they’d put in the script, ‘Mork does his own thing.’ That never happened. You can’t write and prep and rehearse a show not knowing what you’re going to do. A director not knowing what they’re going to block. The other actors not knowing what was going to be said. What would happen, is that you’d begin the week of filming with a Monday morning table read and no matter how funny Robin thought the script was—by Wednesday when we’d go down to watch the rehearsal, the crew got tired of laughing at the jokes, so he’d ask for new jokes. We’d stay until 2 am Wednesday night rewriting the script to fix issues we saw in the script, often to trim down, but also to give Robin new jokes. On Thursday, we’d go down and watch that rehearsal, and rewrite all the jokes we thought were so funny at 1:00 am the night before. On Friday, we’d have the performance before a live audience.

There were two filmings, a 2 pm and a 7 pm. The 2 pm filming got the audience you could get at 2 pm: the old and the infirmed and the recently paroled. They weren’t a laugh-ready crowd. So, Robin would ask for new jokes. Between the two fillings, we’d provide more jokes. And Robin never forgot a joke, so during the 7 pm filming – when we always got a much better audience – he’d mix and match everything we had written. On take 1 he might do a Monday joke, on take 2 he might do a Wednesday joke, and so on. This happened every week. The audience must have been sitting there thinking, ‘Why would you need writers for this guy?’ He would, though, occasionally adlib a joke that made it into the script.

I sure as f#@k have an opinion about this. It has been a constant over the years. The best thing one can do is join The Writers Guild. You have to report these things, you have to watch out for them. Don’t write things for big-name producers on spec. We’ve been asked to do free polishes on drafts when it’s contractual how many drafts and polishes we do. It is very frustrating. There’s an old joke, that writers on set are the whores that have stayed for breakfast. It’s how we’re viewed by execs and some directors in features, like, ‘What are you doing here.’ Now in television, it used to be that a show was run by producers who’d hire staffs of writers, but now showrunners are coming up through writing. Today, virtually all showrunners come up through writing—which is a good thing.

Black and white image of people on a set.

You are touching on a central conundrum. Yes, it is a net gain. There’s more product than ever. It used to be, with a network show, you’d get hired for a season of 22 episodes. Now with streaming it is usually only eight or ten. While the number of shows and films has gone way up, the pay has not [risen] consistent with it. On the other hand, it’s important to get in the club. The produced club. And once you’re in, a lot of doors open up—you now have the cred to be able to pitch your ideas to producers and studios because you have been deemed as a professional. That hasn’t changed, but all in all, it is an infinitely better time to be a writer right now than it has been in 40-some years.

There’s a wealth of very good television on right now. There is so much to choose from. Though, many nights, I’ll be flipping through Netflix, and nothing will appeal to me. On the other hand, when you land on something binge-worthy, it’s like Christmas morning.

One thing about HBO, which was the first pay-cable network to do original programming, is that they really pushed the boundaries of what television could be. They began to win all the Emmys, and I mean, it was not even close. It forced the other networks to not be so bound by standards and practices, to take on more adult themes, to be edgier. That has upped everyone’s game. I think streaming is the most liberating platform to work in, creatively. But this boundary push is still going on, and has created a wonderful time creatively to work within the industry, doing things that are challenging, intelligent, and thematic.

Furthermore, before streaming, networks preferred shows that weren’t serialized. They preferred franchises that you could drop into at any point and still be enjoyed. Part of the reason for this was the after-market, in terms of syndication. This allowed the purchaser, the syndicating buyer, to show them in whatever order they wanted. The first basic cable show to push against that model to an extreme was Breaking Bad. That whole series was a cliffhanger that built off the episodes that came before each new one every week.

Duckman, Meet Joe Black, and Moonlighting.

A lot like Jordan Peele, I’m a horror geek. I’m very dark. I can’t tell you why, but it’s been that way since childhood. The things I write tend towards psychological thriller… that play on or against audience expectations. I love genre, especially horror. Genre storytelling, in many ways, is just the most stripped-down and atavistic. Good genre appeals to you on an emotional level. We go to a comedy to laugh, a tragedy to cry, but more than anything we go to the movies to be thrilled. Moved. To feel like we’ve had an emotional charge. The Greeks called it catharsis, that’s where we get the word, from Greek playwrights who understood the need to make an emotional connection with the audience. Genre to me is the best way to achieve that. But that said, everything comes down to theme. What is the big idea underneath? That’s what dictates the protagonist and the obstacle you put in front of that protagonist.

Close to ten years.

One of my former students from Art Center/College of Design got a job there and he was asked to set up a writing track, and he contacted me and asked if I would be one of the first mentors.

Oh gosh, maybe 20-25.

I love when I work with someone who has a different perspective or traffics in a world I know nothing about. That’s the reason I taught for so many years. I love learning. When you help solve other people’s problems, you keep certain narrative muscles sharp. You can be dropped into other people’s worlds and points of view and that is fascinating to me.

I take them through, ‘what’s your big idea,’ we define the protagonist, and then we define the protagonist’s goal, and finally we define the obstacle to that goal. Define the need and create the obstacle. I have them expand those initial thoughts into three sentences that represent the acts and the beginning, middle, and end, then I have them expand those into three paragraphs. Then a treatment to fill in some of the details and have enough to write a draft. I just kind of take them through each step, keeping in mind the greater arc of the transformative journey of the protagonist—be it small or large. We basically build a house together. By the end they have a first draft, though some mentees have stayed with me and come back for a second pass.

It’s one-on-one. That’s tough to beat. To have the dedicated attention of someone with experience in the world you want to be in. As a mentor, it’s more than just discussing the building blocks of narrative, you’re able to have the freedom to go off in any direction the student need, untethered from a strict curriculum. In a class you just don’t have the ability to devote this kind of time to one student. It’s unprecedented attention from a working professional.

I have two pieces of advice. One is mine, one is the best advice I was ever given.

My piece of advice is to remember that no one wants to read your script. Write that on a Post-it, put it on your computer screen: “no one wants to read your script.” When you give someone your script, you’re basically giving them a two-hour homework assignment. On top of that, you’re giving them the added homework of taking notes and sitting down with you and discussing the project. Before you know it, you’re asking someone to give up a half a day of their life. Why? Why should I or anyone else do that? What is it about your script that’s worth a day of my life? Meaning you have to write to excite and compel the reader from word one. I really hit the importance of the first ten pages. That you need to grab the reader by the lapels, not let go, and you make a pact with them; put this script down at your own risk. And you renew that pact with them every ten pages. Just because you’ve written something all the way to fade out, doesn’t mean anyone, even the person you’re sleeping with, has to read it. No one wants to. It’s your job to make them want to.

The second piece of advice. The best I was ever given. It was given by Gary Belkin. He was talking about sitcom scripts, but it’s true of features, it’s true of everything. The traditional way to break into the television market was to find a show that spoke to you—either a drama that had the gravitas that felt right to you, or a comedy that had your particular sense of humor. Find a show that is a good fit for you, and you write the best version of that show you can. And if in all objectivity, after you finish that script, you can sit back and read it and say you did justice to that show – if it’s a drama, you’ve done a story that’s every bit as dramatic and serves the cast in the same way they do each week, if it’s a comedy you’ve written solid jokes and serve that cast as well – if you’ve done all that? You have failed. They’ve already got a staff doing that. What is new and different you bring to that mix? Where is your voice in that? What is new and different? Don’t sit down to write as good as what you see — sit down to write better than what you see.

Ron Osborn has established a significant legacy in American television and film, primarily as a producer and writer. His career spans decades, marked by involvement in culturally impactful shows like “Moonlighting” and “Duckman: Private Dick/Family Man,” as well as feature films like “Meet Joe Black.”

Osborne’s early career involved foundational work as a Story Editor and Executive Story Consultant on series like “Mork & Mindy” and “Night Court.” These roles honed his understanding of narrative structure and television production, paving the way for his later success as a writer and producer.

Transitioning to writing, Osborne contributed to “Night Court” before gaining widespread recognition for his work on “Moonlighting.” He served in multiple writing capacities, shaping the show’s unique blend of comedy, drama, and meta-narrative elements. His contributions earned him two Primetime Emmy Award nominations for Outstanding Writing in a Drama Series.

Osborne’s creative talents extended to animation with “Duckman,” a series he developed and for which he served as the Writer (Creator). This animated show allowed him to create a satirical comedic world, earning him a CableACE Award for Best Animated Programming Special or Series. He also ventured into film screenwriting, co-writing the screenplay for “Meet Joe Black.”

Beyond writing, Osborne made significant contributions as a producer. His involvement with “Moonlighting” evolved to include Senior Producer and Producer roles. For “Duckman,” he served as Executive Producer, providing leadership for the series. His other producing credits include “Cupid” and consulting producer roles on various series.

Osborne’s contributions have been recognized through numerous awards and nominations. He received multiple Primetime Emmy Award nominations for “Moonlighting” and “Duckman,” securing a win for Outstanding Animated Program. He also won a CableACE Award for “Duckman.”

His involvement extended beyond television and film, contributing to the “Duckman” video game adaptation. He also served as an Executive Consultant on “Good Witch,” demonstrating the continued value of his experience.

Osborne’s career has left an enduring mark on American television. He played a vital role in the success of “Moonlighting” and spearheaded the critically acclaimed “Duckman.” His ability to transition to film and co-write screenplays for notable productions highlights his versatility.

Beyond his on-screen work, Osborne has also contributed to the education of aspiring filmmakers, teaching screenwriting at institutions like the Art Center College of Design and DreamWorks. His global seminars further demonstrate his commitment to sharing his knowledge.

In conclusion, Ron Osborne’s career as a writer and producer has been marked by significant achievements and lasting contributions. His work on iconic shows and films solidifies his place as a notable figure in the history of American entertainment.

1987 Outstanding Writing in a Drama Series Moonlighting Nominee Writer

1987 Outstanding Writing in a Drama Series Moonlighting Nominee Writer

1987 Outstanding Drama Series Moonlighting Nominee Producer

1986 Outstanding Writing in a Drama Series Moonlighting Nominee Writer

1986 Outstanding Drama Series Moonlighting Nominee Producer

1997 Outstanding Animated Program (For Programming One Hour Or Less) Duckman Nominee Executive Producer

1996 Outstanding Animated Program (For Programming One Hour Or Less) Duckman Nominee Executive Producer

1994 Outstanding Animated Program (For Programming One Hour Or Less) Duckman Winner Executive Producer

Ron's Business of Screenwriting Digital Download Screenwriting Course is Available Exclusively Through The Film Connection

Film Connection © 2025 | All Rights Reserved | Built with 💙 by DesignTork